Well... this is definitely a longer post than last month's! I've read a few more novels this month than in February, mostly due to me finding a new series I like and binge-reading most of it.

So here come my mini-reviews of the books I read in March, and in case you're interested, here are the other posts so far from this year:

January,

February

The Boatman's Daughter by Andy Davidson (2020)

I’ve fallen really behind with my Abominable Book Club reading (that’s the amazing monthly horror book box that I subscribe to). I’ve got a few months’ worth of books from them to read – all of which look great – and so I thought I’d make a start on catching up this month. The first one I read was the featured book a couple of months ago.

The Boatman’s Daughter is the story of Miranda Crabtree (the daughter of the title). It begins with Miranda accompanying her dad on a job – he is taking the local ‘witch’ out to perform some clandestine service for Billy Cotton, the local (unhinged) preacher. Things take a pretty unpleasant turn early on, setting in motion a dark tale in which Miranda is forced to take on horrible work for horrible people, before realizing that things have to change if she’s going to ensure her survival (and the survival of those she cares for). That plot summary is a bit rubbish, to be honest, but I don’t want to give too much away. The dark, unsettling pleasure of

The Boatman’s Daughter lies in its

feel as much as its plot. The book is Southern Gothic, but in the best possible way. It’s full of sleazy darkness, the oozing murk of the bayou, and crumbling old buildings that house really nasty secrets. And, like all good horrors, the shadowy supernatural threats are utterly overshadowed by the human ones. It’s darkly lush and really quite compelling. Definitely recommend this.

Deity by Matt Wesolowski (2020)

The next book I read was also from the Abominable Book Club, but it was actually the featured book in this month’s parcel. Despite still having some books to catch up on, I couldn’t wait to read

Deity. It appeared to have been written especially for me.

Deity is the fifth book in Wesolowski’s

Six Stories series (though you don’t need to have read the others). The series premise is that online journalist Scott King presents a podcast exploring the darker mysteries of the online world. Each story is presented through six interviews, each offering a different perspective. It’s

Rashomon for the internet age. I was completely intrigued by this premise (and if you’ve read my blogs before you’ll know how much I adore unreliable narrators/narratives). And I was not wrong to be intrigued – this book was absolutely right up my street.

Deity has Scott King explore the case of Zach Crystal, an enigmatic pop star who died amid a flurry of #MeToo allegations. The book came out in late 2020, and it’s understandably been described as ‘timely’. It opens with epigraphs from books about Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson, but I suspect they were added shortly before publication. Wesolowski’s Zach Crystal is an amalgamation of elements inspired by other pop culture stories (not least a certain iconic pop star who was…

bad?), but with a very British backstory.

Deity is incredibly readable, and I loved it. And I bought the rest of the series the minute I’d finished it!

Shame on You by Amy Heydenrych (2017)

For reasons best left unsaid, I jumped away from my Abominable Book pile and grabbed the first eBook to hand. This next one was on Prime Reading, and I chose it because the blurb looked the most intriguing of the available titles (and I know, I know, I said I wasn’t going to do that again). Heydenrych’s novel is about Holly Evans, a lifestyle influencer who has amassed large numbers of followers on Instagram and YouTube. Holly posts food videos, espousing a vegan, raw food, clean eating diet that – raise your eyebrows here – she says helped to her to beat cancer without the aid of chemotherapy or other chemical intervention. However,

Shame on You doesn’t start with Holly’s rise to social media fame. It starts with a dishevelled and bleeding Holly stumbling into McDonald’s one night after being attacked. What could have led to this? And is Holly’s social media life somehow to blame? Actually… you don’t have to read very much of the book to find out the answers to this, as the circumstances of the attack and the motivation of the attacker become apparent very early on. Sadly, what isn’t said outright in the first couple of chapters is pretty easy to deduce.

Shame on You has an interesting premise, but the execution is rather pedestrian and lacking in surprise (unless you count my surprise that, despite knowing her attacker has been in her flat, Holly never once considers

calling a locksmith). Not a strong recommendation from me.

Six Stories by Matt Wesolowski (2016)

So after that slightly random departure, I went back to Matt Wesolowski’s series and started at the beginning.

Six Stories is Wesolowski’s debut novel and the first in a series of (at the current time) five books. It was little weird reading

Six Stories having already read

Deity, though I can’t explain exactly why that was without giving a major spoiler. This did make me wonder what it would’ve been like to pick up

Six Stories without any preconceptions, but it also made me realize that this is a series that can stand being read out of sequence.

Six Stories follows the same format as

Deity – a mystery is explored and discussed via interviews on a podcast, and each of the six chapters is an ‘episode’ of the show. The mystery here is the death of teenage Tom Jeffries, who disappeared during a trip to Scarclaw Fell and whose body was found a year later. Podcast host Scott King speaks with people who knew Tom, or who were involved in the case, to try and get to the truth of the case. There’s plenty here about the complexity and nuance of teen dynamics, but also a healthy dose of sinister folklore and urban legend, particularly focused around the supposedly supernatural threats that lurk on Scarclaw Fell. The mystery here held, perhaps, fewer surprises than

Deity (and some things were quite obvious early on), but the way the story is told is just captivating, and I really couldn’t put it down.

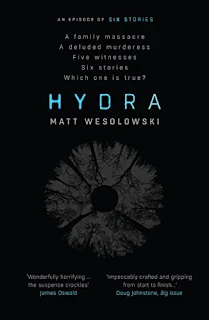

Hydra by Matt Wesolowski (2017)

After

Six Stories, I went straight into the second book,

Hydra. And I think this one is my favourite of the three I’ve read so far. Following the same format as the other books,

Hydra sees Scott King look into the ‘Macleod Massacre’ of 2014. A young woman named Arla Macleod killed her family in a shocking and frenzied attack. She was found guilty of manslaughter by reason of diminished responsibility and sent to a secure unit. But why did Arla do it? Is ‘psychosis’ enough of an explanation? Spoiler alert: no, ‘psychosis’ is not enough of an explanation, and the book does an admirable job of attempting to cut through some of the panic induced by the word (though I will say, as a minor criticism, it doesn’t go far enough and still relies on the idea that ‘psychosis’ only exists in the super-scary hallucinations-and-violent-delusions flavour, ignoring the somewhat more mundane breaks from reality that are more common). That said, I enjoyed the way the book’s fictional podcaster pushed to get under the skin of Arla’s story, revealing some pretty horrible things in the end. While

Six Stories and

Deity cloak their stories with a folk horror fog,

Hydra draws on urban legends, creepypastas and internet games (Black-Eyed Kids, the Korean Elevator Game). It was also nice to see the first appearance of Wesolowski’s own antichrist superstar Skexxixx, who appears in

Deity as well. This fictional character is turning out to be way more sympathetic than his real-life counterpart!

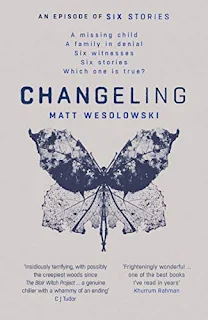

Changeling by Matt Wesolowski (2018)

I really have just ploughed on with Wesolowski’s series, haven’t I? I’m finding them a bit moreish! And I’m now really not sure whether

Hydra is still my favourite, or whether it’s been usurped by

Changeling. I’m definitely noticing some themes that run through the

Six Stories series as well. While the mysteries in each book have a hint of the supernatural, they all have a very human heart, dealing with social issues that are both current and, sadly, deep-rooted. There’s a recurrent sympathizing with the disenfranchised – particularly children in care – and an implicit criticism of just how much of blind eye is turned when someone is exhibiting behavioural problems indicative of trauma. But all the books also reveal a fascination with both traditional and contemporary folklore and, strikingly, terrifying forests.

Changeling has all of this in spades: podcaster Scott King investigates a thirty-year-old missing child case. One night in 1988, little Alfie Marsden went missing from his dad’s car on the edge of Wentshire Forest Pass (and Wentshire joins

Six Stories’ Scarclaw Fell and

Deity’s Crystal Forest as a place of sylvan terror and folk legend). But there’s more to the story than just the threat of the forest’s fair folk. I’ll admit to spotting the secret here, though I wasn’t totally sure that it was really going to go where I suspected. But it did, and the ending packed the punch I was anticipating. As with the other books in the series, I couldn’t put this one down.